Astrophotography from Linz –

Fascinating astrophotos

Dr Dietmar Hager’s astrophotos are a special kind of experience. Taken under the best conditions, these photos provide rare insights into our cosmos.

Fourteen astrophotographs by Dr Dietmar Hager, most of which have been awarded prizes by NASA, can be admired in the STERNWERKSTATT pop-up gallery in the Linzerie from 23 November to 30 December (Mon-Sat, 10:00-12:00, 16:00-19:00). The works can also be purchased online in the STERNWERKSTATT webshop. The large-format pictures are limited, certified and available in customised frames.

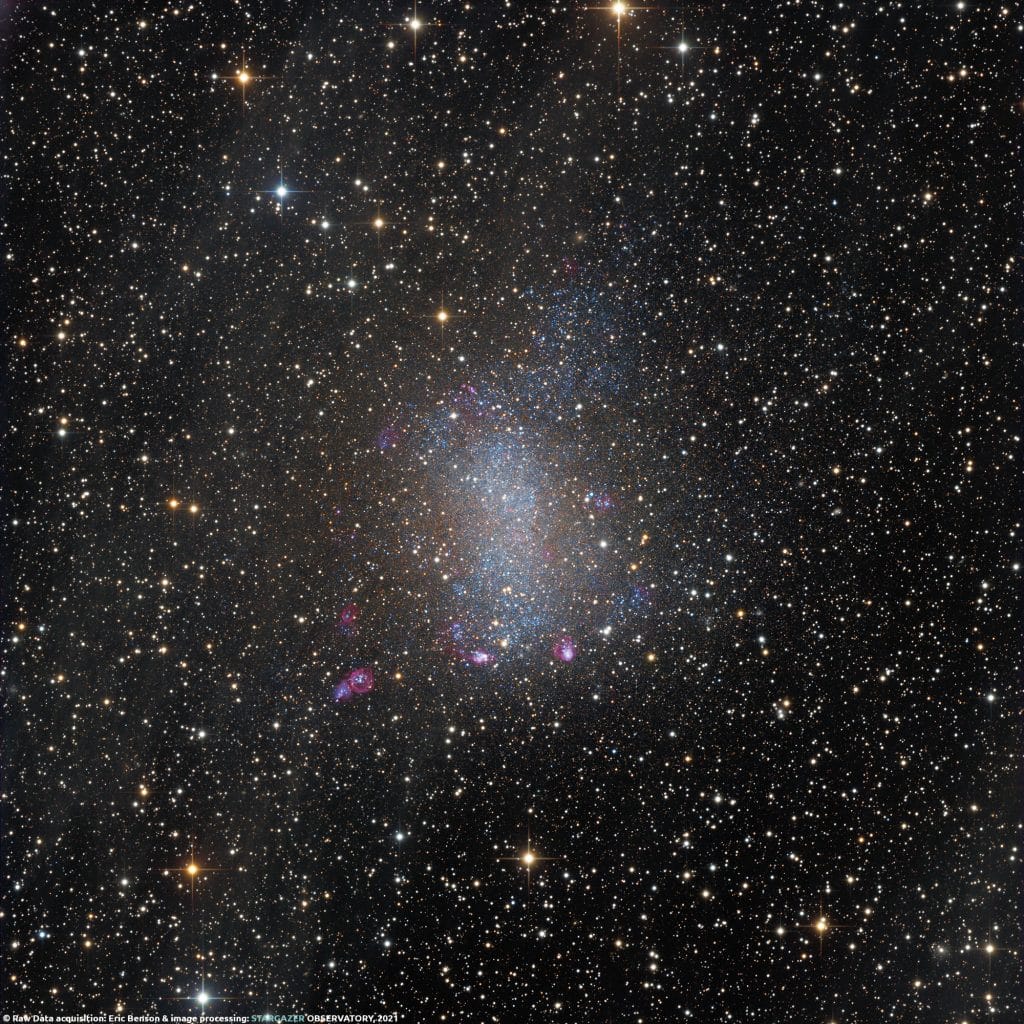

NGC 247 is actually quite a small galaxy in the southern night sky and, like Jonah or Pinoccio, is located in the whale. More precisely, in the much larger constellation ‘Whale’.

This galaxy was discovered as early as 1784 by the German-British astronomer and musician William Herschel. It is part of the Sculptor group of galaxies (which also includes the two galaxies NGC 253 and NGC 55) and is therefore

close to the so-called Local Group, to which our Milky Way also belongs.

Close means that the galaxy NGC 247 is only around 10 million light years away from us, so we can also recognise many details in its ‘body interior’. We can see many small pinkish-red regions. These are hydrogen clouds in which new stars are being formed. Some people are familiar with similar regions from the well-known Orion Nebula, which is located just around the corner in our galaxy at around 1,350 light years. We also see light blue regions, which are highly active young and hot groups of stars.

In addition to NGC 247, this image shows a number of other galaxies that are much further away, i.e. ‘behind’ NGC 247 and therefore appear small.

The fact that we can recognise so much detail in this photo is not only due to the relative proximity of NGC 247 to us, but again due to the excellent image material from Eric Benson in the Australian desert. The photo is based on a total of 30 hours of exposure time, divided into around 100 individual frames in 4 colour groups.

This photo is again a joint project by my Australian colleague Eric Benson and Stargazer Observatory – Dietmar Hager.

The US astronomer Halton Christian Arp has also rightly included this galaxy as Arp 153 in his well-known catalogue of ‘peculiar galaxies’. Arp 153 was discovered in 1869 by the Scottish astronomer James Dunlop in the constellation Centaur.

This galaxy, also known as Centaurus A, is part of the M83 group. It is described as a huge elliptical galaxy located at a distance of around 12 million light years from Earth. Other data speak of a distance of up to 17 million light years. It is the closest galaxy of this type to Earth.

As a radio galaxy, NGC 5128 is the third brightest radio source in our sky and is also a strong source of X-rays and gamma rays.

NGC 5128 aka Arp 153 has an angular extent of about the size of the moon and, with an apparent brightness of 6.6 mag, is no longer visible to the unaided human eye. Nevertheless, Centaurus A is one of the apparently brightest galaxies and thus belongs to the group of the brightest extragalactic objects in the night sky.

Its characteristic optical features are, on the one hand, the clearly visible dust band that crosses the galaxy. Secondly, a relativistic jet is emitted from the core. Due to its proximity, it is one of the best-studied active galaxies. A black hole with a mass of 55 million solar masses is suspected at its centre.

My colleague Eric Benson has succeeded in obtaining extremely flawless raw image material from his remote observatory in Arkaroola, about 700 kilometres north of Adelaide. This data made it possible to painstakingly visualise the effects of the aforementioned nuclear jet, which can even be seen in visible light.

The galaxy NGC 3923 shown here is located in the constellation Hydra (water snake) and is at a distance of over 90 million light years from Earth.

This is an elliptical galaxy, which is an example of a shell galaxy similar to those we know from onions. These shells can also be recognised in this image.

It is not yet entirely clear how these shells are formed. It is assumed that this is due to so-called galactic cannibalism. A larger galaxy swallows the smaller accompanying galaxy ‘When the two centres approach each other, they first oscillate around a common centre, and this oscillation ripples outwards to form the stellar shells, just as ripples spread out on a pond when the surface is disturbed.’ (quoted from https://esahubble.org/images/potw1519a)

Once again, many, many hours of image collection have gone into this picture: Over 80 hours in total! This image of NGC 3923 is a co-operation project with my Australian colleague Eric Benson, who is responsible for the raw data.

The photo shows a gravitationally bound triplet of galaxies that are part of the NGC 3169 group in the constellation Sextant: NGC 3169, NGC 3166, NGC 3156.

The spiral arms of NGC 3169 are literally being pulled out by gravitational interactions with the neighbouring galaxy NGC 3166 and appear as sweeping tidal tails. Both galaxies are striving inexorably towards the fate of one day merging into one galaxy. Compared to the Milky Way, these are small galaxies, with the larger of the three having a maximum size of just 70,000 light years.

What is striking in this image is the so-called ‘galatic envelope’, which presents itself here as a veil. This envelope is formed by individual stars that have been torn out of the galaxies and now form this veil as ‘orphaned star nations’.

This formation was discovered by the German-British astronomer, musician and composer Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel on 19 December 1783.

This image is special for us star photographers simply because of the enormously long exposure time. This photo contains a total of 87 hours of pure exposure time, which is divided into L, R G and B.

NGC 6729 is a nebula located in the constellation ‘Corona Australis’. This yellowish-white nebula, which is also known as number 68 in the Caldwell Catalogue, is part of a whole group of so-called reflection nebulae and surrounds the variable star ‘R Coronae Australis’. NGC 6729 was discovered in 1861 by the German astronomer and geologist Johann Friedrich Julius Schmidt.

The ‘Corona Australis’ is also known as the ‘Southern Crown’, the counterpart to the ‘Corona Borealis’, the ‘Northern Crown’. This ‘Southern Crown’ is just visible from our latitudes, it is slightly south of the constellation Sagittarius and therefore just above the horizon. In Australia, this constellation is high in the sky, which is why the raw data for this image was again obtained in collaboration with Eric Benson in the Australian desert.

This star R in the constellation Corona Australis is a double star system whose brightness varies between 10th and 14th magnitude, which is a difference of 100 times, as this brightness scaling is logarithmic.

Scientists are also interested in this nebula because there is a star-forming region at its centre that can be observed and studied very well due to its proximity to us.

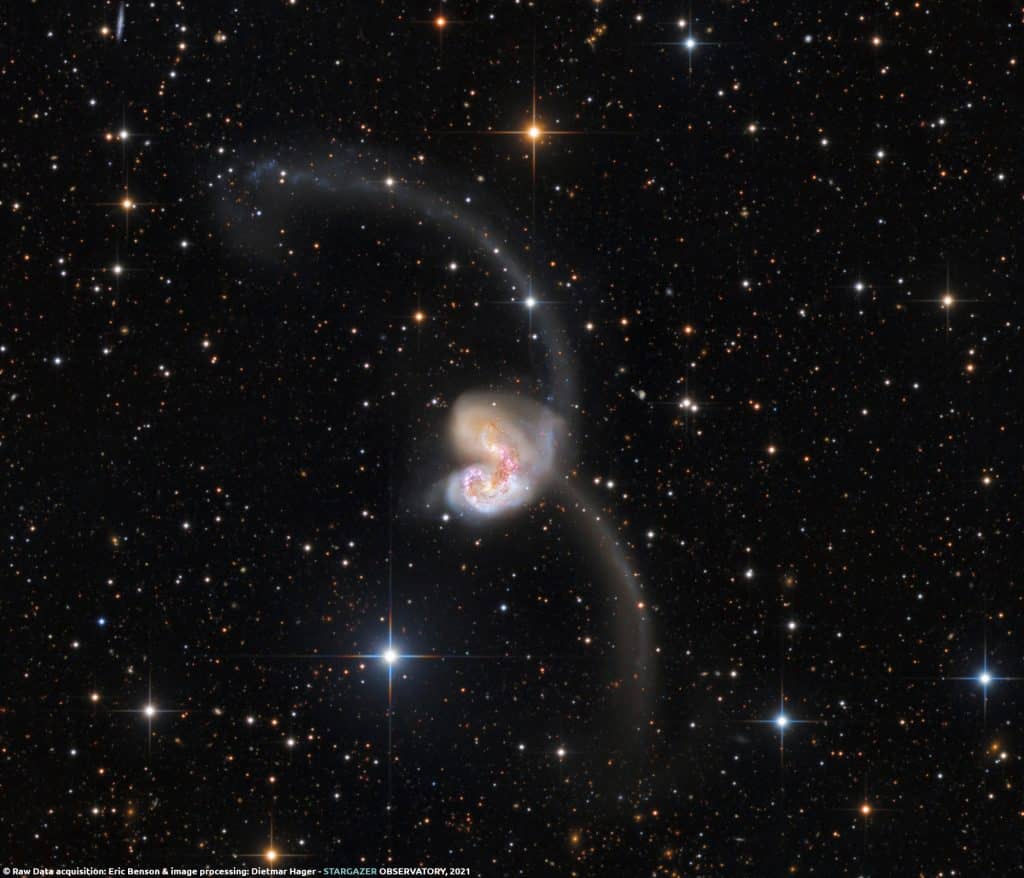

This special form of galaxy is a so-called antenna galaxy. Although this image was taken in the Australian desert, we can also observe this special form of galaxy here in the northern hemisphere, albeit very close to the horizon.

Arp 244 is one of the many galaxies discovered in the 18th century by the German-British astronomer and musician Wilhelm (William) Herschel, a true galaxy hunter.

It consists of the two galaxies NGC4038 and NGC4039, which have collided and are now interpenetrating. To be precise, it is not the planets of the two galaxies that are colliding, but their large clouds of dust and gas. Here we also find star formation processes in progress. This collision takes some time; it is estimated here that it is an event that takes around 1,000,000,000 years.

The beautiful and clearly visible antennas of this galaxy consist of matter and new star clusters that have been flung far away by gravitational tidal phenomena and now form these special, striking arcs.

Incidentally, such an encounter is also imminent for us. Our Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy are currently on a collision course and are approaching each other at a speed of several thousand kilometres per second, a speed that we can hardly imagine. Nevertheless, it will still take some time for the two to find each other: The rendezvous will still be a few billion years away.

This photo is again a joint project by my Australian colleague Eric Benson and Stargazer Observatory – Dietmar Hager and is based on around 88 (!) hours of pure exposure time over a period of several years.

This photo was also published again by NASA as the ‘Astronomy Picture of the Day’.

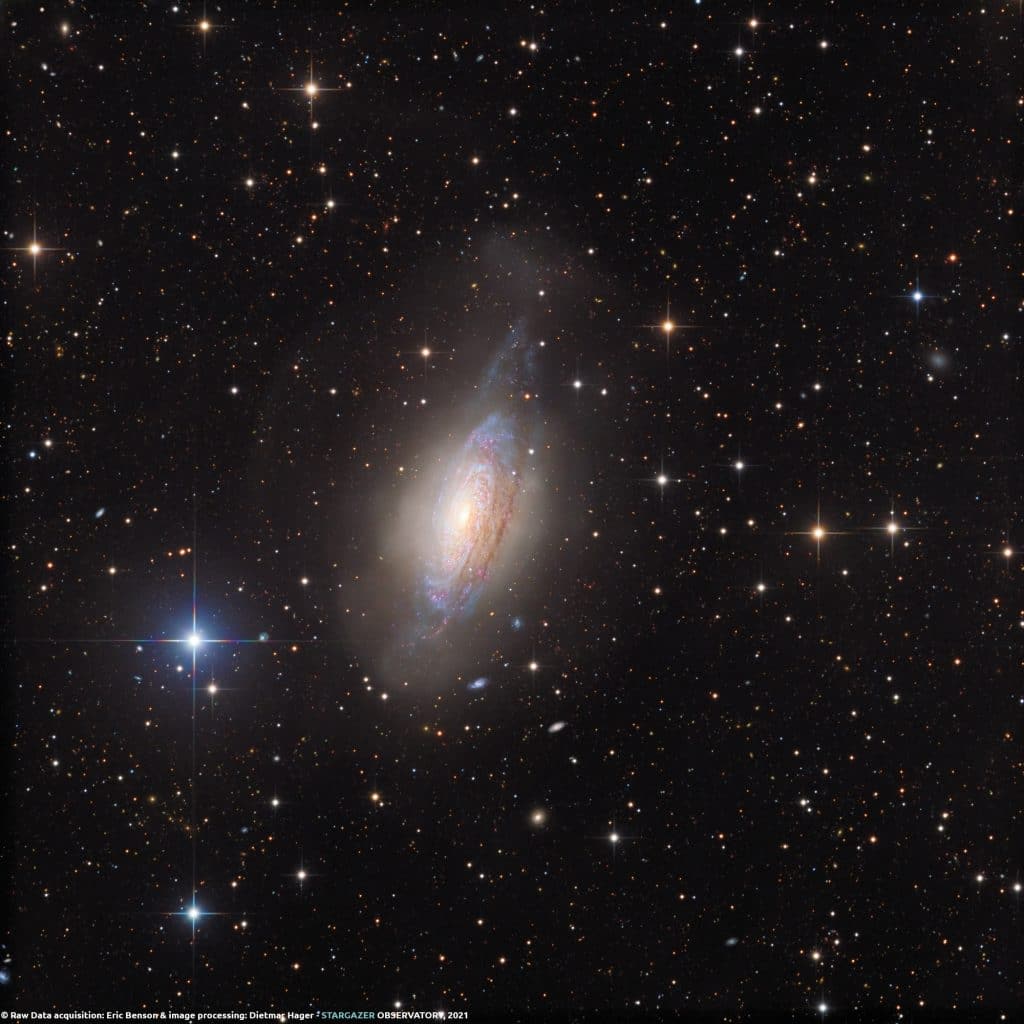

In 1784 there was no internet and the telescopes and telescopes were a little more modest than those of today. And so this beautiful galaxy had to wait a long time before it came to worldwide attention.

On 25 February 1784, it was again the German-British astronomer and musician William Herschel who discovered this galaxy in the constellation Leo. It is located at a distance of around 35 million light years and can already be found in the night sky with smaller, modern telescopes.

NGC 3521 has an extent of around 50,000 light years and shows us its characteristic, irregular spiral arms. This galaxy is somewhat similar to ours in terms of size and appearance, with the

difference that NGC 3521 has already had a somewhat more violent encounter with another galaxy, which can still be recognised on the right of the image as an oval (egg-shaped) homogeneous collection of light. Incidentally, our Milky Way is also yet to have such an encounter, even if it will still take a few billion light years until then.

In the spiral arms of NGC 3521 we find a lot of dust as well as pink-coloured star-forming regions and clusters of young, blue-appearing stars.

35 million light years away … This means that the light that we have captured here in our photo comes from a time when our Alps still resembled a young, gentle, romantic hilly landscape.

This photo of this galaxy required around 20 hours of total exposure time, split over many individual nights and

many more hours of image processing before we were able to coax this jewel out of our night sky.

This photo was also published again by NASA as the ‘Astronomy Picture of the Day’.

NGC 1365 is a galaxy in the constellation of the ‘Oven’.

We are hardly familiar with this zodiac sign because it hardly ever rises above the horizon.

This alien Milky Way is about 60 million light years away, i.e. we see its light, which has been travelling to us since the time when the Alps were forming on Earth and the Mediterranean was filling up.

Looking out into the depths of the universe is always an encounter with history. And even if this light is so old, we can learn a lot from it! A suggestion to political decision-makers: pick up the history books, read and learn from the mistakes of others.

In Arkaroola in Australia, in an environment where there is practically no light pollution, Eric Benson collected a total of almost 20 hours of exposure time in many individual black and white frames. I was allowed to edit these images together with Torsten Grossmann. Achieving this very good image result was difficult this time, as the signals in the parts containing the colours were very weak. And the core also gave us a hard time – because there was an extremely large ‘dynamic range’. This means that the core is exorbitantly brighter than the rest of the galaxy. Image processing was therefore a particularly big challenge.

Would you like to read more about this galaxy? Take the time to look it up on Wikipedia, for example.

This beautiful Milky Way is very close to our own, as it unfolds its full splendour in the constellation of the Sculptor at just under 12 million light years. Hence the name.

We are not quite familiar with this sign in our latitudes, as it barely rises above the horizon.

In this image, which contains a total exposure time of almost 20 hours, this galaxy is shown in the apparent size of the moon.

We see many young hot star populations (blue fields) and the royal resident ‘old lords’ of the star clusters in golden yellow colour.

The special thing about this Milky Way is that you can see a very impressive band of dust here. This galactic dust is ‘sacred’ for every galaxy, as it gives rise to new star systems, among other things.

On prolonged observation, one gets the impression that some of these dust structures flow out of the Milky Way at right angles to the longitudinal axis like ‘chimney smoke’.

In the background there are numerous other Milky Ways, but they can only be recognised as tiny, comma-like structures, as they are several billion light years away.

The image data was taken by my friend Eric Benson in his remote-controlled observatory and sent to me. To my great delight, the data was excellent, making it easy to create such a beautiful image.

The Sombrero galaxy gets its name from the fact that in a small telescope it only shows visually the part above the broad dust band and looks like a Mexican sun hat: a sombrero.

It is a very old galaxy that shows a huge dust band in its equator, which is excellently suited for radio astronomy and precise measurements.

Namely, measurements that reveal that everything in space is in motion and that even galaxies do not stand still. This is remarkable because – unfortunately – the term ‘fixed star’ still appears in textbooks; however, this should be cancelled, because: Nothing in the universe is fixed or firmly anchored, except the laws of nature, which can be observed everywhere.

The largest globular cluster in the Milky Way – a huge cluster of stars. Globular clusters are among the oldest inhabitants of our Milky Way. As the name suggests, they represent a giant cluster of stars that present themselves in a spherical shape. For a long time it was not understood how stars that appear so densely packed can remain stable over billions of years. A simple relationship between space and time clarifies this. Based on great data material from the centre of Australia’s extremely dark hinterland. More information: e.g. on Wikipedia.

The Sombrero galaxy gets its name from the fact that in a small telescope it only shows visually the part above the broad dust band and looks like a Mexican sun hat: a sombrero.

It is a very old galaxy that shows a huge dust band in its equator, which is excellently suited for radio astronomy and precise measurements.

Namely, measurements that reveal that everything in space is in motion and that even galaxies do not stand still. This is remarkable because – unfortunately – the term ‘fixed star’ still appears in textbooks; however, this should be cancelled, because: Nothing in the universe is fixed or firmly anchored, except the laws of nature, which can be observed everywhere.

Barnard’s Galaxy is a small, yet very special feature in the starry sky. Located in the constellation Sagittarius, it is very close to us. Only about 1.5 million light-years separate NGC 6822 from us, making it, along with the Magellanic galaxies, one of the closest galaxies to us.

This galaxy was discovered in 1884 by the American astronomer and pioneer of stellar photography, Edward Emerson Barnard. At that time, it was still unclear whether it was a galaxy. Today, we know of approximately 10 million stars within it, and with a diameter of almost 8,000 light-years, it is considered a dwarf galaxy.

This proximity of NGC 6822 allows us to even find globular clusters in the image and to resolve them optically.

Although this irregularly shaped dwarf galaxy is small, it is a highly active galaxy in star formation, as evidenced by its blue regions. Blue stars are almost always very hot, active stars. We also see numerous pink hydrogen glows from star-forming regions.

To the left and slightly above in the image is a nebula area, which, together with the numerous stars in the foreground, belongs to our galaxy.

This photo is again a joint project by my Australian colleague Eric Benson and Stargazer Observatory – Dietmar Hager.

This photo was also published again by NASA as the ‘Astronomy Picture of the Day’.

This group is made up of the galaxy NGC 3511 (in the lower part of the photo) and the galaxy NGC 3513 (in the upper part of the photo). Both galaxies are so-called barred spiral galaxies, located around 45 million light-years from our Milky Way. At the center of the galaxy NGC 3511 we also find a so-called supermassive black hole. If you look for it, you will find it in the constellation of Crater (often referred to as the constellation of Crater). Although the NGC 3511 group lies south of the celestial equator, parts of it can sometimes be seen from the northern hemisphere. The two galaxies were discovered on December 21, 1786, by the German-British astronomer and musician William Herschel.

NGC 6822 Barnard’s Galaxy in the constellation Sagittarius ‘A very strange looking galaxy.’ is what you might think when you see photos of NGC 1316. How did this galaxy, also known as Arp 154, come into being?

NGC 1316 was discovered by James Dunlop in 1826 and has puzzled scientists ever since. The galaxy NGC 1316 is part of the constellation Fornax, which is only visible in the southern hemisphere. The galaxies of the Fornax galaxy cluster are also very close at around 60 million light years.

The shape suggests that the galaxy first collided with another galaxy several billion years ago and then merged with it. In the course of time, other smaller galaxies were added. This elliptical galaxy is one of the brightest sources in the radio range and thus represents a textbook example of a so-called radio galaxy.

NGC 1316 ist ein begehrtes Studienobjekt, da sich an ihr physikalische Prozesse und Abläufe studieren lassen, wie sie bei Verschmelzungen und Galaxienentwicklungen geschehen. So ist NGC 1316 Forschungsgegenstand des Kartierungsprojekts Meerkat Fornax Survey, ein vom Europäischen Forschungsrat gefördertes Projekt, das auf Beobachtungen mit dem Meerkat-Teleskop des South African Radio Astronomy Observatory in Südafrika basiert.

This pair of galaxies in the constellation of the Great Bear, which is also home to the Big Dipper, is one of the most beautiful objects in the northern starry sky. The two are located around 12 million light years away from us and are part of a neighbouring group of galaxies known as the Virgo Cluster.

On the left you can see the spiral galaxy M81 from an oblique perspective. With large spiral arms and a bright yellow core, the diameter is around 100,000 light years. On the right is M82, which can be recognized by the red gas and dust clouds.

The two galaxies have been locked in an incessant gravitational battle for a billion years. The respective gravity influences the other galaxy in cosmic close encounters. Their last orbit alone lasted around 100 million years and most probably led to the formation of the large number of spiral arms that we see today. In the M82 galaxy, we find enormous star-forming regions and colliding gas clouds. These are so energetic that the galaxy literally glows due to the X-rays emitted.

In the next billion years, their gravitational struggle will lead to a merger and only one galaxy will remain.

Both galaxies have been photographed by us before and can be viewed here on this page.

This photo was also published again by NASA as the “Astronomy Picture of the Day”.

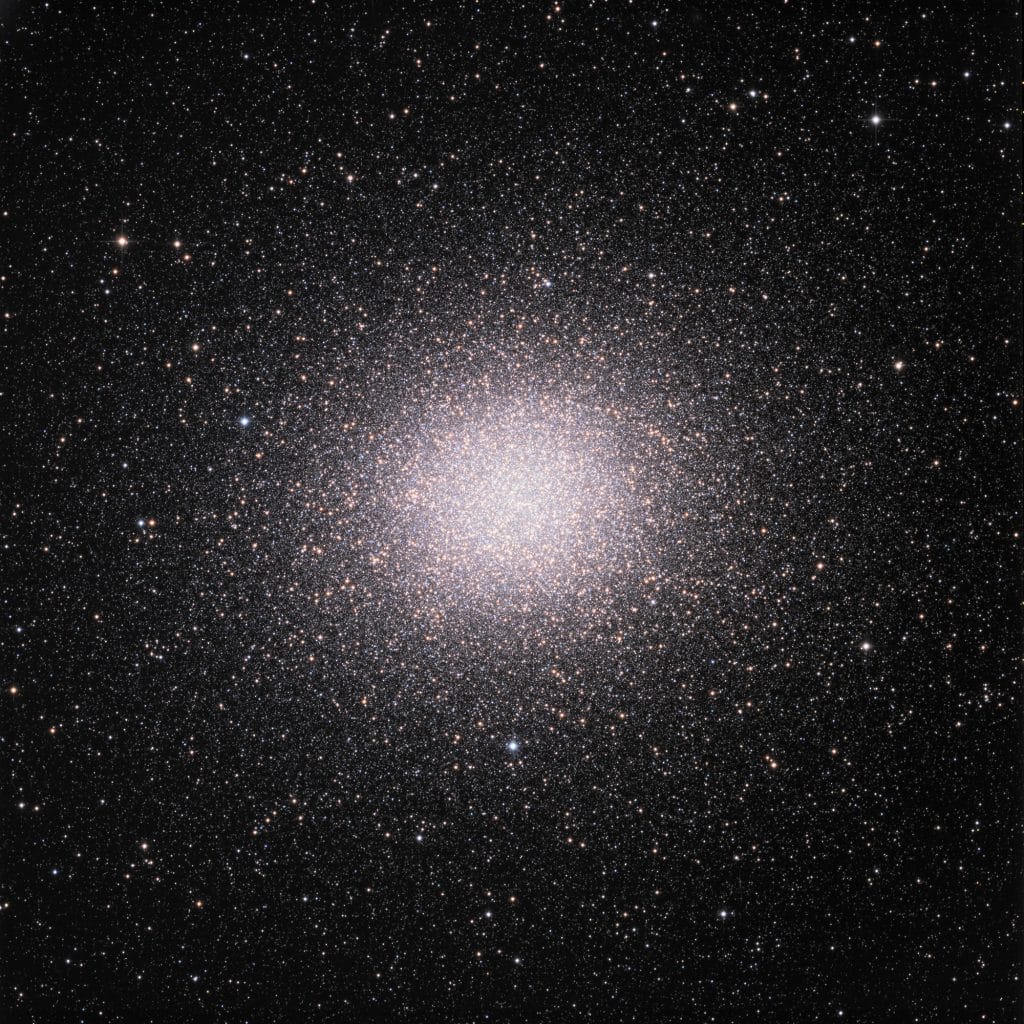

434 years ago, the German astronomer Johann Abraham Ihle (1627-1699) discovered this object in the evening sky. M 22 is a so-called globular star cluster in the constellation Sagittarius and is so bright that it can even be seen with the naked eye.

The interesting thing about this object is that it is one of the first globular clusters in which more than one black hole has been discovered. This is unusual in that it long contradicted current astronomical models and the understanding of a globular cluster. The reason for this is that the object M 22 was not expected in purely mathematical terms. On the basis of the computational estimates available until not so long ago, it was thought that black holes within a globular cluster would bring it into an unstable situation. In short: calculated unstable situation = object cannot actually exist.

The existence of M 22 proved that the mathematical models had to be revised. We now know very well that globular clusters in particular are extremely old. Globular clusters are as old as the Milky Way itself and therefore twice as old as our solar system.

M 22 is almost 10,000 light years away and measures about 100 light years across! In the evening sky, this results in an apparent size equal to that of the moon.

Keep an eye out for the object with your binoculars! With a little research on the Internet for star charts, you can definitely find Messier 22 in the constellation Sagittarius near the center of the Milky Way in the sky!

With one very important prerequisite: you have to get out of the city’s light pollution!

This photo is again a joint project by my Australian colleague Eric Benson and Stargazer Observatory – Dietmar Hager.

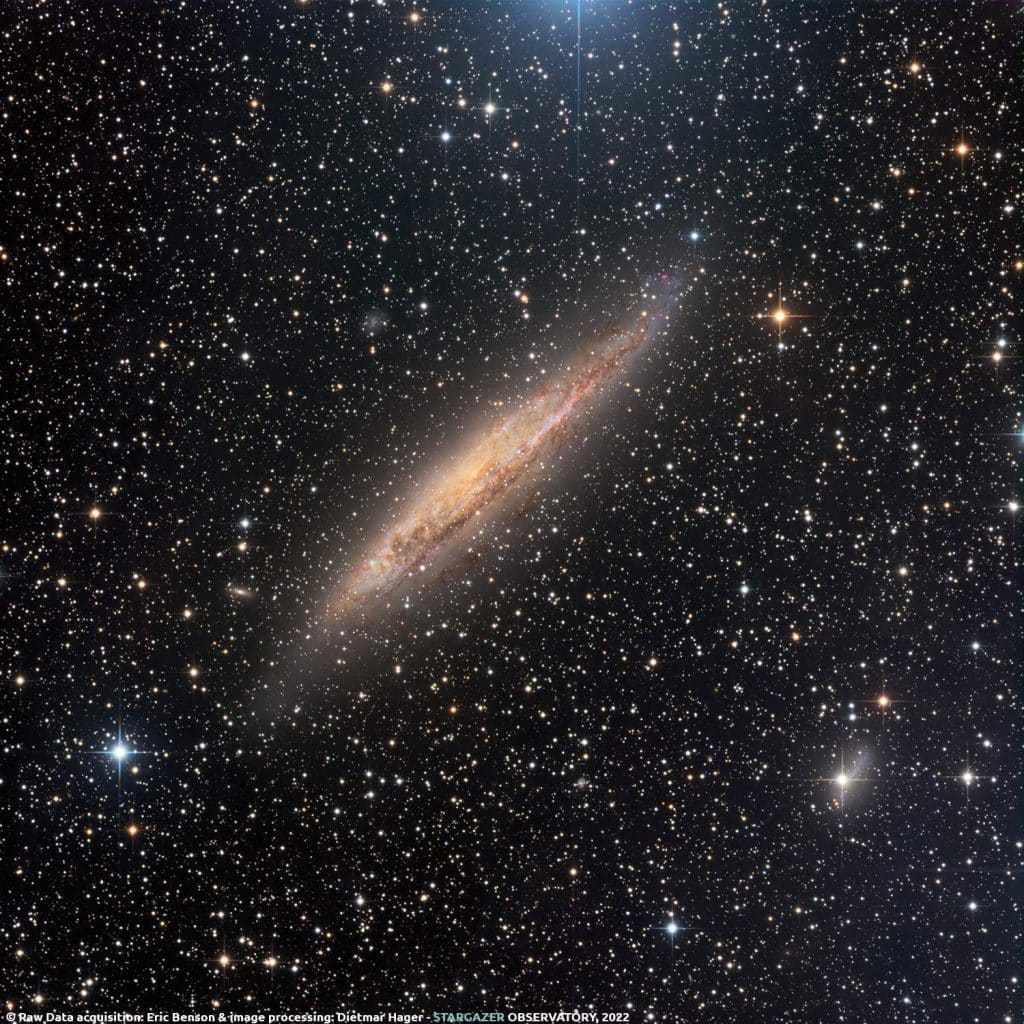

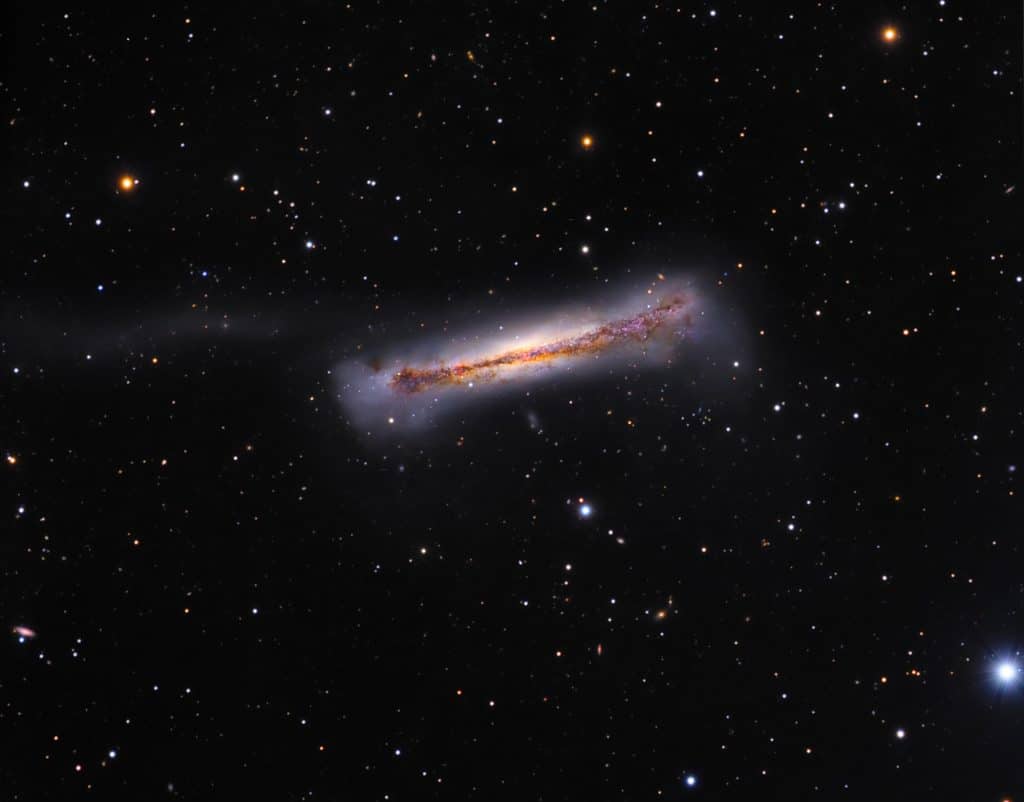

This galaxy was discovered in the early 19th century and is a rather small but particularly interesting galaxy in the constellation “Sculptor”. Small, because it is not even half the size of our Milky Way. If you are looking for it, you have to look for an apparent moon size in diameter.

NGC 55 is almost impossible to observe in our evening sky because it is so low in the sky. That’s why the raw image material was again collected by my Australian partner Eric Benson in the outback and processed by me into this image.

At only 4 million light years, NGC 55 is also quite close to us and can easily be observed in a standard telescope. The location should be as far south as possible and no light pollution should impair the view.

The special feature of this galaxy are the so-called “star clusters”, which can be resolved very well photographically. They are recognizable as solitary, highly luminous blue dots, which are particularly concentrated around the core of the galaxy, but also in the periphery.

NGC 55 also shows numerous incredibly large hydrogen regions, recognizable as pink structures; these represent star-forming regions.

When observing NGC 55, you should definitely also take a look at the surroundings of the galaxy, as a number of equally well-resolved galaxies can be seen here (e.g. bottom right in the image). The most distant objects are quasars, which appear as dark wine-red spots in the left-hand field of view. These are about several billion light years away.

Here we see the result of 25 hours of total exposure time, divided into 30-minute frames.

In autumn 2019, this painting will be presented to the public at the Ars Electronica Center in Linz.

The picture is also available in a larger size: Contact

This large spiral galaxy in the constellation of the Big Dipper has been known to astronomers for almost 250 years. It was discovered at a time when it was en vogue to look out for comets.

In order not to confuse potentially new comets with already known objects, “fixed” objects were cataloged. The so-called Pinwheel Galaxy was given the catalog number M101, an abbreviation for the catalog named after the French astronomer Charles Messier.

The apparent size of M101 in the night sky is comparable to that of the moon. And this despite the fact that it is about 17 million light years away! Size matters…

The image is the result of a collaboration between Torsten Grossmann and Stargazer Observatory. We are looking at an image with a total exposure time of about 10 hours, divided into numerous individual exposures that have been systematically processed into a final image. A 7″ TMB Apo refractor, i.e. a classic refracting telescope, served as the imaging device under the night sky about 60 km south of Berlin

Seeing conditions during HA-data acquisition below average, transparency very good. Seeing conditions for R, G average. Seeing conditions for B and L fine. Transparency in RGB very good. Moon present while imaging L and B. The Crescent Nebula, aka NGC 6888, is a very well renown and most intriguing object located in the constellation “swan” in the northern hemisphere. At an apparent size of about 18 by 13 arc-minutes it is a very pale nebula. Even in a moderate amateur telescope you cannot see this nebula. One would need absolute dark skies (or narrow band filters) and a decent “light buckett” to glimpse the nebula visually. It’s absolute diameter is some 25 by 18 light years. Gazing at NGC 6888 means we are looking 4700 years into the past. NGC 6888 renders a nebula coming from the blueish star at the center. And this is known to once have been a super-giant star. That means the star has had a giant mass! Small stars like our sun dwell some Billions of years with their fule. Super Giant stars are kind of play-boys, as they deplete their fule at “full speed”. And in this particular case the central star qualifies for being summed upon the socalled “Wolf Rayet” stars. After only a coule of Million years the fule is almost used up and the star is standing right before a significant change: it is gonna go supernova quite soon, spoken in cosmological terms, though. So, at present we are looking at a star that vents its outer layers into space at terrific speed and therefor the star sustains severe loss of mass. The gas is holding lots of oxygen and hydrogen, just before the individual big “bang” of the WR-star. Read an intriguing story about the Crescent-nebula written by Tammy Plottner from UT.

Who knows the constellation of the water snake? Only a few in our latitudes, as it comes into view quite low on the southern horizon. Yet it contains one of the most beautiful Milky Ways that can be observed.

From a distance of 15 million light years, this majestically beautiful galaxy presents itself in its full expansion. As it is relatively close to us, it belongs to the so-called local galaxy group and is therefore a sister galaxy to the one in which we live. The image shows numerous nebulous formations that appear reddish or pinkish red. These are exciting areas, comparable to the well-known Orion Nebula; they are star-forming regions in a foreign Milky Way that we can nevertheless photograph from Earth. If they could be observed with the naked eye, they would make up about 1/3 of the full moon in the night sky.

In cooperation with Eric Benson, one of my astrophotography friends from Australia, I took this picture. Eric runs a remote observatory in a light-polluted area of Australia where M83 shows up high in the sky.

There is also a fire wheel galaxy of the north. I also photographed this a long time ago. See also: http://www.universetoday.com/17824/the-firecracker

20″ CDK reflector telescope, FLI CCD camera, LRGB image data. Processed in CCD Stack, Pix Insight and Photoshop. Image acquisition: Eric Benson, image processing: Dietmar Hager.

(Torsten Grossmann) and 9″ TMB Apo Fall 2011 NASA APOD

Messier 82 is one of my favorite galaxies because it is such a beautiful target for visual observation! The galaxy is located in the constellation of “Big Bear” aka as “big dipper”. You can spot the spectacular galaxy in a strong bino already. But when you observe M82 in a decent telescope of powerful light-collection capacity, it revelas a lot of the dust-lanes!

M82 is a so-called star-burst galaxy. This means that stars form at a significantly higher and more intense rate than in galaxies of comparable mass. One tends to believe this is linked to a dramatic gravitational effect, caused by the interaction with “near-by” M81. However, neary-by means 12 Mio light years. M82 is one of the best investigated “star-burst-galaxies”.

The redish areas in the image represent Hydrogen that emits strongly infrared and radiowaves. Thie close encounter of the two neighborghing galaxies is fabled to have taken place some 400 Mio years ago. Based upon observations in near infrared-, infrared- and radiospace telescopes as well as X-ray examinations the core of the galaxy might hold more than only one supermassive black hole.

Far to the right in the image you can identify a bit of a lighter area in space. This is not an artefact but a result of the tidal-effects based upon the gravitational interaction of the two galaxies M82 and M81.

Date: December 2008 + January 2009 – seeing 5-(7)/10; transp. 6-7/10

Scope: 9″ TMB Apo f/7 using TeleVue 0,8 reducer

CCD: SXV H16 L:3.5h 1×1; 1.7h 2×2 each color RGB

(10 min subs) no darks in 1×1, 3 darks in 2×2.

Software: Astroart 4, CCD Stack, CCD Sharp, Registax and Maxim DL

Processing: postprocess in PS CS2, Pix IS LE

M81 is probably one of the most popular galaxies among the celestial objects of the Northern Hemisphere. Discovered by Johann E. Bode in 1774, M81 is located in the constellation “Big dipper”. Shining at 7m0 visually she makes a wonderful target for a bino-viewer, as this sprial-galaxy is considerably large, measuring ~ 27×14 arc minutes (compare the full moon appears at 31 arc minutes). At a distance of about 12 Mio light years, this galaxy is a bout 4 times more distant than the famous Andromeda galaxy, the largest galaxy visible from the Northern Hemisphere. M81 is only the most prominent “star” of a bunch of galaxies, called the M81-group: M82, NGC 2403, NGC 2976, Holmerbg IX, NGC 3077 and others render further members of this group. In a decent amateur telescope (above 16″ aperture), however, M81 reveals her entire beauty, as you can then gaze into the spiral arms and see the very bright core, that, by the way, houses a super massive black hole, which comprises perhaps 100 Mio solar masses.

In regards to gravity, M81 is engaged to M82, respectfully. Actually these two are bound together by gravity and therefor rotate around a common center of gravity, bringing them quite close to each other. At present (presence would be what we humans of the 21st century can gather now) our own galaxy, the Milky Way would merely fit inbetween M81-82; expressed in numbers we are looking at 120,000 light years distance between the two. M81-82 is fabeld to have gone through a severe interactive gravitational encounter some hundreds of million years ago. As a result, huge masses of gas, dust and also stars are strewn inbetween the two galaxies. Whenever galaxies collide or at least come close to each other, serious changes take place, metamorphing the original phenotypical appearance of both galaxies. Consequently, M82 has turned into a so-called “star-burst” galaxy, nursing now millions of new stars, which could be addressed as “off-spring” of such a galactic interaction.

In the image you might notice a small little irrgular looking structure a little above the galaxy and a little to the left. This object is a small satellite-galaxy of M81, called Holmberg IX, named after its discoverer Erik B. Holmberg, a Swedish astronomer of the last century. Near the bottom and a little to the left is one of a typical background galaxies, named PGC 29505, shining at about 17m0.

When the famous Austrian mountaineer Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner hovers in the highest mountains of the world, she might be able to spot this galaxy with bare eyes!

September + October 2009 NASA APOD

Discovered in 1784 by William Herschel, this spectacular galaxy is located in the constellation “pisces”. Holding 7.6 arc minutes by 2.8 arc minutes she is not exactly large, but rather bright as its apparent magnitude measures some 10m7, being about 24 Mio light years away from Earth. As a result of these numbers we find NGC 660 to hold about 36,000 light years in diameter.

NGC 600 is counted among the so-called “polar-ring-galaxies”, which is something peculiar among all galaxies known at present: Basically two galaxies were about to merge entirely, but by gravitational means of “dark matter” they have gotten “arrested” while undergoing the process of melting together. In an advanced stage of such unification both galaxies are believed to no longer proceed further into each other. NGC 660 is also a strong candidate for a search for compact radio sources.

This image shows the beautiful galaxy group “Deerlick” in the constellation “Pegasus”.

Torsten Grossmann and I collected image data with our respective observatories. Torsten photographed south of Berlin with his 7 inch TMB Apo. 15×15 min luminance and 11×8 min each red, green and blue. At the foot of the Hansberg in the Mühlviertel I collected CCD data (7 hours) with my 9 inch TMB Apo One-Shot Color.

As always, the picture is a joint production by Torsten Grossmann and Dietmar Hager.

Located in the constellation Cygnus, some 1200 light years away, this planetary nebula, aka PK93+5.2, H I-192, h 2099, GC 4627 is a most spectacular object for a powerful telescope (say larger than 16″ aperture). It appears rather bright in a 20″ dobsonian, as its visual magnitude is 10m7. In blue, however, it is only 13m3 bright. It holds 1.4 arc minutes in diamter which is considerably large for a PN.

Discovered by William Herschel in 1787 the distinctive shape of the nebula donates the name, reminding the observer of an embryo. The dark hole which can be seen very well in the image near the center, origins back a long time ago, when a seperate nova blew this part of the nebula up.

August to October 2009: 16″ RC + Astrodon LRGB

14x lum @ 1×1, 600s

11x red @ 2×2, 600s

25x green @ 2×2, 600s

35x blue @ 2×2, 600s

Software: AstroArt4 image acquisition, CCD Soft, preprocessing in CCD Stack, Maxim Dl, CCD Sharp; postprocessing in PS CS4.

This fantastic galaxy can be spotted in the constellation “Lynx” in the Northern Hemisphere. To perceive the light visually you would however need a telescope, as the brightness is limited by 9m7. At a distance to Earth of about 27 Mio light years the apparent size of this galaxy measures 9.3 arc minutes by 2.2 arc minutes. That of course means we are looking at the galaxy almost from the edge. Like in so many cases of first human ever to lay eyes on this object was Wilhelm Herschel on 5th of February 1788. Those days back the galaxy was considerably closer to earthbound observers, as NGC 2683 receded at the tremendous speed of about 400 kilometers per second. For earthlings 3 Billion kilometers sounds a lot, but considering the huge distance of millions of light years, this is practically insignificant.

Have you noticed the background galaxy group to the left? There is a region of very small reddish objects in the upper left quadrant of the field. These galaxies have been measured to some 4.3 Bio licht years away from Earth. That means, the light that reaches us nowadays comes from a time, when Mother Earth was about to be formed (thanks Mischa Schirmer for looking up the data).

This image shows us a section of the sky in the constellation “Hydra”. This constellation is practically only easily observable from the southern hemisphere.

My colleague Eric Benson collected wonderful image data there in Australia, which I have processed into this picture.

The special thing about these objects is that we see stars on them that are in the immediate vicinity, i.e. a few light years away. In the background are Milky Ways, which are just recognizable as dark red dots. Due to the enormous distance, these Milky Ways are shifted far into the red light. The distance is over 8 billion light years!

No other picture on my website shows such enormous contrasts in terms of distance.

The two main objects are NGC 5101 (top right) and NGC 5058, both of which are Milky Ways similar to the “ours” we live in. Their light, which Eric collected over a period of almost 30 hours in his observatory in Australia, comes from a time when the Mediterranean had just formed on Earth and when there were no Alps. So about 100 million years ago.

We can see 5058 quite precisely from the side (edge-on position), and 5101 almost directly from “above”. Both are barred spiral galaxies.

Scattered throughout the image are many more distant galaxies. The larger ones, which give color and shape, are several hundred million light years away.

All in all, the saying by the most important cosmologist of the Renaissance, Giordano Bruno, applies to this picture: “The sun with its planets is only one of myriads of stars in a universe that knows no boundaries”.

This picture is dedicated to the mother of my children: Christine.

This majestic spiral galaxy, which we view exactly from the edge, is staged in an adequate constellation (Lion), suiting the huge size of NGC 3628. The longitudinal diamter is barely about 1/4 of the apparent size of the moon. That makes her pretty large! This said, and knowing that NGC 3628 shines at 9m5 visually, which is pretty bright for a galaxy that is roughly 35 Mio ligh years away from our place, one still cannot understand, why Mr. Messier did not mention the galaxy in his famous catalogue, though he did so with the neighbouring very famous ones (M65,66), only half a moon away from the location.

BTW: These three are supposed to interact by gravitational means. There is evidence for such interaction, as you can find a faint so called “tidal trail” of stars to the left. These represent stars that have been distracted by gravitational force of M65, 66. Like in so many cases, it was Wilhelm Herschel who discovered NGC3628 in 1784.

Should you be interested in a comparison with an older image taken with a one shot color CCD from Starlight Xpress SXVF M25C then please click the line “One shot color Image SXVF M25C (2007)” above.